She spent part of the afternoon just looking through the old box in which she kept those special things. Little memories tied up inside the clipping from The Land newspaper. There was the browned paper with the copy of Walter’s description of Winton: “The district in which I live.”

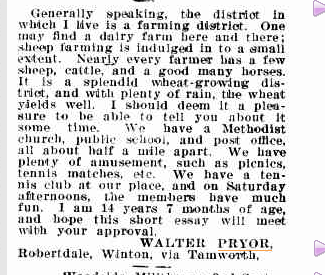

Generally speaking, the district in which I live is a farming district. One may find a dairy farm here and there; sheep farming is indulged in to a small extent. Nearly every farmer has a few sheep, cattle, and a good many horses. It is a splendid wheat growing district, and with plenty of rain, the wheat yields well. I should deem it a pleasure to be able to tell you about it sometime. We have a Methodist church, public school, and post office, all about a half a mile apart. We have plenty of amusement, such as picnics, tennis matches etc. We have a tennis club at our place, and on Saturday afternoons, the members have much fun. I am 14 years 7 months of age, and hope this short essay will meet with your approval.

Generally speaking, the district in which I live is a farming district. One may find a dairy farm here and there; sheep farming is indulged in to a small extent. Nearly every farmer has a few sheep, cattle, and a good many horses. It is a splendid wheat growing district, and with plenty of rain, the wheat yields well. I should deem it a pleasure to be able to tell you about it sometime. We have a Methodist church, public school, and post office, all about a half a mile apart. We have plenty of amusement, such as picnics, tennis matches etc. We have a tennis club at our place, and on Saturday afternoons, the members have much fun. I am 14 years 7 months of age, and hope this short essay will meet with your approval.

WALTER PRYOR Robertdale, Winton, via Tamworth.

Robertdale, Winton: the farm she’d had to buy back from the estate of her husband Robert who’d been killed in an accident loading the big, rammed, four bushel bags of wheat at a rail siding 12 years ago in 1904. Left with a dozen children, she had plenty ahead of her; the hollowness at the loss of thirteen year old Stanley, dying down in Newcastle in 1912, barely over a year since Walter had written his description: proud and optimistic as one born just ahead of the new nation.

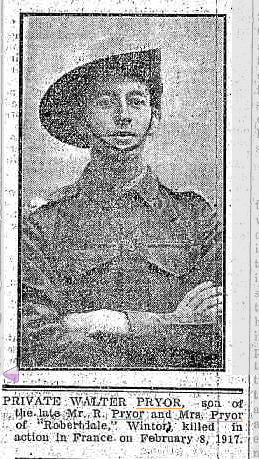

The glint of a smile was there for a moment and then gone; chased away by the emptiness she felt at the imminent farewell for the boys. The members of the tennis club and other guests were to be on hand to say goodbye and good wishes to Walter and his elder brother Robert Oliver, who were now, just like the trees that dotted their wheat paddocks: Kurrajongs. The Kurrajongs was the name the 33rd Battalion had chosen for itself as it drew on the farms, towns and villages of the New England and North West. There was the fresh photograph of Walter in his new uniform, nineteen years old.

Fine speeches were given and entertainments from local amateurs. Farewell gifts were presented, with Robert being given a fountain pen, and Walter and the other boys were given money belts and ‘soldiers comforts.’

It seems the thing to do; she knew that everybody was sending their men off to be part of the great struggle they by now, as 1916 ended, were imagining in much more real terms as the lists of dead and maimed grew on the pages of the newspapers.

Just as he was barely twenty, the telegram arrived. Walter Pryor, killed in action in France; February 8, 1917.

Just as he was barely twenty, the telegram arrived. Walter Pryor, killed in action in France; February 8, 1917.

His elder brother Robert Oliver was wounded in France and then passed away in England of pneumonia while being treated.

While the bulk of young Australian men enlisting in the army during World War One, the ‘Great War,’ came from cities and urban areas, there is still a romantic notion of the adventurous spirit and strong, larrikinism with a willingness to thumb a nose at convention. It was expected that the young country boys would demonstrate the resourcefulness, marksmanship and horsemanship held in high regard by their families and be great warriors for their country’s pride and, most particularly, to the protection of the Empire.

There is rarely a town or village where there is no sad memorial to the dreams and nightmares of great loss. The little crosses, benign beside names yet potent in the sadness they can evoke.

As we move toward the remembrance of ANZAC Day and its place in our history, let us never forget the very human faces that can be there; frozen in time.

They shall grow not old;

nor will my Great Uncle Walter.

And for my Great Grandmother, twenty years to carry on.